Books Books Books! A Children's Librarian and life-long book addict invites fellow readers to share their thoughts on books and library service to children and young adults. You'll find musings on and reviews of books for children, teens, and adults. Dedicated to all those who would rather be reading.

Monday, October 31, 2011

8:45 am to 9:45 am - reflection

In a perfect world, my job would include an hour or two reserved purely for thinking, reflecting, planning, and mulling things over. Some of this thinking would be targeted at particular issues facing existing or upcoming programs - trouble-shooting, fine-tuning, problem-solving, and improving - but some of the reflecting would be unfocused and undirected. How lovely it would be to feel free to wonder "what if..." and see where that question takes me.

As is the case for so many people these days, the reality is that there isn't enough time in the day to spend on all the projects I'm responsible for, much less time to dream and ponder. Surely this is a problem! There is great pressure for libraries - and for my library system in particular, which is trying valiantly to pull itself out of a slump caused first by a decades-long, head-in-the-sand culture and now by terrible budget woes - to be innovative. Yet can there be innovation and creativity if we're fighting hard just to keep our noses above water?

As I've gotten older, I've discovered some truths about myself, some of them rather dismaying. The main thing I've learned over the past 5 years is that I'm simply not creative in that brilliant, lightbulb-flashing-on way that I so admire in others. I don't get sudden fabulous ideas. I'm not going to be the one who comes up with an amazing new service model that wows the crowds at a future ALA conference. (Well, never say never - I could be a late-bloomer, right?)

Luckily, along with the sad self-revelations come positive ones as well. For instance - it has become more and more clear to me that not only do I do my best work when collaborating with others, but I love it. For an introvert who felt for years that I could be happy shelving books all day long if I could get a decent wage for it, this is Big News. And happy news, too - because my colleagues are intelligent, hard-working, and (most importantly) brimming with amazing, creative ideas. Aha!

So my tiny Youth Services staff met with a handful of fiercely dedicated YA Librarians on Thursday and with similarly enthusiastic Children's Librarians on Friday, and together we created the outlines - and even fleshed in some details - of what will be a terrific 2012 Summer Reading Program. My job was to lay out all the things we needed to discuss and decide - and then guide the discussion, coax out details, keep folks on track and enthusiasm high...

...and then get to the unglamorous task of turning all the great ideas into a program we can implement. Because that's another one of my strengths - being practical and hard-working.

But to help transform LAPL into not just a well-functioning library system but also a dynamic and responsive one, I need to encourage the creative people around me to share their ideas with me and prod me into figuring out a way to make them happen.

And even a busy workhorse like me needs some time just to dream and ponder.

What if...?!

Saturday, October 29, 2011

Child characters, adult books

I've just read two books, one right after another, in which the main character is a young person, and yet both books are for adults. Weirdly, both books are almost exactly the same size, being somewhat smaller and having fewer pages than most adult books.

In Matthew Kneale's When We Were Romans, a 9-year-old British boy named Lawrence writes of the tumultuous, confusing time when his mother drove his little sister and him to Rome quite suddenly. Lawrence understands that they are fleeing the threat of his father, who has separated from his mother but who is apparently stalking the family.

What Lawrence doesn't understand, though the reader slowly does, is that Lawrence's mother is mentally ill. At first she seems to be a fine and loving mother who is perhaps a bit paranoid or overly worried - but through the course of the novel, it's clear that she is seriously disturbed. Lawrence is an extremely intelligent, sensitive, and appealing boy - but though he finds some things about his mother's statements and behavior illogical or strange, he has neither the perspective nor the desire to understand that there are some big problems here. Instead, he has no choice but to embrace her delusions entirely.

Older teens would surely read between Lawrence's slightly misspelled but precocious lines and know that Lawrence's mother is spiraling out of control. Teens are also just far enough from childhood themselves that they can empathize with Lawrence's point of view while also seeing the limits of his understanding. As well, teens will enjoy the added layer of meaning created by Lawrence's delicious descriptions of various tyrants, gleaned from the Hideous Histories series he is reading. Would a child actually write this way? Well, no - and yet, there is a decidedly young flavor to the narration, with its breathless sentences, misspellings, and childish phrasing.

This book is about adults - their manias, their relationships, and the way children are dragged along in the wake of their dramas. But teens, while not as autonomous as adults nor as likely to be parents, won't find the situations incomprehensible. In fact, I'm betting many older teens would enjoy this book quite a bit. It would make a fine book to discussion in an English class.

Quite different is Megan Abbott's The End of Everything. Told from the point of view of 13-year-old Lizzie, it's about the apparent abduction of her friend Evie. Abduction of teen girls is a common theme in YA fiction (think Living Dead Girl by Elizabeth Scott and Stolen by Lucy Christopher, to name just a couple). So why is this particular book meant for adults?

The story takes place in the 1980s, and though the 13-year-old narrator tells of events in the present tense, there is no feeling that this is a 13-year-old voice. Lizzie's choice of words, her sentence structure, and her preoccupations all give the feeling is of an adult looking back at a very intense and life-changing time.

One of the main themes running through this novel is the awakening of sexuality in girls, and this tinges the narration with a diffuse, lush, awkward, and sometimes uncomfortable sensuality. Lizzie is at the end of her childhood and she knows it, yet she also knows how very much she doesn't know about sexuality. This confusion feels both familiar and stylized to me as an adult reader. That is, I remember the confusion, excitement, frustration, and fear of being 13 - but if I had been asked to describe it, I would have blinked in astonishment. The sophistication of Lizzie's narration is masterful - and not necessarily something that teens themselves, even older ones with a bit more perspective, would recognize or relate to.

Then there's the "abduction" of Evie (by a neighbor named Mr. Shaw), which is inextricably linked for Lizzie with Evie's father Mr. Verver, Evie's older sister Dusty, and with Lizzie's intense and incoherent feelings about these people. There is strangeness here - Evie sort of sees it and the reader definitely does. It's nothing definite, and yet most readers will feel very queasy indeed about how the charming and undeniably great Mr. Verver relates to his daughters and to Lizzie. As for Evie and Mr. Shaw - well, the mystery is not so much in what happens as in Evie's thoughts and reactions to what most would agree is a heinous crime.

Teens have read with great interest Emma Donoghue's Room, Alice Sebold's The Lovely Bones, and other adult books about intensely disturbing situations involving teens or young women. There's nothing in this book that is any worse than those, and I suspect many older teen girls will in fact read this one as well. I'm not sure, though, that the revelations will hit readers of this age with quite as much force as they would older readers. Sure, there is the intrigue and nastiness of the basic situation - but it's all the subterranean currents that make this a powerful read, and I'm not sure teens would be as apt to pick up on them.

Each of these two books is clearly meant for adults, but with characters, themes, and a smaller size that make them possibly intriguing to teens as well. Do we recommend these and other adult books to older teens? It depends on the book and on the teen, of course - but in general, I like the idea of guiding teens to the bounty of the adult fiction shelves. While they may have already discovered adult genre fiction (fantasy, horror), it's a bit more daunting to find those small gems hidden among the Stephen Kings and George R.R. Martins. Short, well-written books with young main characters are natural bridges, even if they contain adult themes that teens may not have the experience or perspective to fully appreciate.

In Matthew Kneale's When We Were Romans, a 9-year-old British boy named Lawrence writes of the tumultuous, confusing time when his mother drove his little sister and him to Rome quite suddenly. Lawrence understands that they are fleeing the threat of his father, who has separated from his mother but who is apparently stalking the family.

What Lawrence doesn't understand, though the reader slowly does, is that Lawrence's mother is mentally ill. At first she seems to be a fine and loving mother who is perhaps a bit paranoid or overly worried - but through the course of the novel, it's clear that she is seriously disturbed. Lawrence is an extremely intelligent, sensitive, and appealing boy - but though he finds some things about his mother's statements and behavior illogical or strange, he has neither the perspective nor the desire to understand that there are some big problems here. Instead, he has no choice but to embrace her delusions entirely.

Older teens would surely read between Lawrence's slightly misspelled but precocious lines and know that Lawrence's mother is spiraling out of control. Teens are also just far enough from childhood themselves that they can empathize with Lawrence's point of view while also seeing the limits of his understanding. As well, teens will enjoy the added layer of meaning created by Lawrence's delicious descriptions of various tyrants, gleaned from the Hideous Histories series he is reading. Would a child actually write this way? Well, no - and yet, there is a decidedly young flavor to the narration, with its breathless sentences, misspellings, and childish phrasing.

This book is about adults - their manias, their relationships, and the way children are dragged along in the wake of their dramas. But teens, while not as autonomous as adults nor as likely to be parents, won't find the situations incomprehensible. In fact, I'm betting many older teens would enjoy this book quite a bit. It would make a fine book to discussion in an English class.

Quite different is Megan Abbott's The End of Everything. Told from the point of view of 13-year-old Lizzie, it's about the apparent abduction of her friend Evie. Abduction of teen girls is a common theme in YA fiction (think Living Dead Girl by Elizabeth Scott and Stolen by Lucy Christopher, to name just a couple). So why is this particular book meant for adults?

The story takes place in the 1980s, and though the 13-year-old narrator tells of events in the present tense, there is no feeling that this is a 13-year-old voice. Lizzie's choice of words, her sentence structure, and her preoccupations all give the feeling is of an adult looking back at a very intense and life-changing time.

One of the main themes running through this novel is the awakening of sexuality in girls, and this tinges the narration with a diffuse, lush, awkward, and sometimes uncomfortable sensuality. Lizzie is at the end of her childhood and she knows it, yet she also knows how very much she doesn't know about sexuality. This confusion feels both familiar and stylized to me as an adult reader. That is, I remember the confusion, excitement, frustration, and fear of being 13 - but if I had been asked to describe it, I would have blinked in astonishment. The sophistication of Lizzie's narration is masterful - and not necessarily something that teens themselves, even older ones with a bit more perspective, would recognize or relate to.

Then there's the "abduction" of Evie (by a neighbor named Mr. Shaw), which is inextricably linked for Lizzie with Evie's father Mr. Verver, Evie's older sister Dusty, and with Lizzie's intense and incoherent feelings about these people. There is strangeness here - Evie sort of sees it and the reader definitely does. It's nothing definite, and yet most readers will feel very queasy indeed about how the charming and undeniably great Mr. Verver relates to his daughters and to Lizzie. As for Evie and Mr. Shaw - well, the mystery is not so much in what happens as in Evie's thoughts and reactions to what most would agree is a heinous crime.

Teens have read with great interest Emma Donoghue's Room, Alice Sebold's The Lovely Bones, and other adult books about intensely disturbing situations involving teens or young women. There's nothing in this book that is any worse than those, and I suspect many older teen girls will in fact read this one as well. I'm not sure, though, that the revelations will hit readers of this age with quite as much force as they would older readers. Sure, there is the intrigue and nastiness of the basic situation - but it's all the subterranean currents that make this a powerful read, and I'm not sure teens would be as apt to pick up on them.

Each of these two books is clearly meant for adults, but with characters, themes, and a smaller size that make them possibly intriguing to teens as well. Do we recommend these and other adult books to older teens? It depends on the book and on the teen, of course - but in general, I like the idea of guiding teens to the bounty of the adult fiction shelves. While they may have already discovered adult genre fiction (fantasy, horror), it's a bit more daunting to find those small gems hidden among the Stephen Kings and George R.R. Martins. Short, well-written books with young main characters are natural bridges, even if they contain adult themes that teens may not have the experience or perspective to fully appreciate.

Wednesday, October 26, 2011

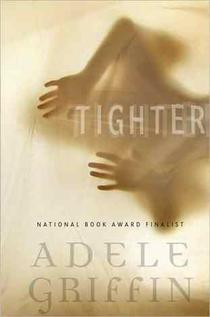

Review of Tighter by Adele Griffin

Griffin, Adele. Tighter. Knopf, 2011.

"You'll have to give this book a try when I'm done with it," I told my 17-year-old when I was halfway through Tighter. "It's creepy - kind of a modern version of Henry James' Turn of the Screw." Which she hasn't read - but after hearing the plot, she agreed that Tighter might be worth a try.

It starts out most promisingly, with a troubled 17-year-old girl named Jamie getting what sounds like a cushy summer job babysitting a rich 11-year-old girl named Isa on a ritzy resort island in New England. Naturally, there has to be a catch. First there's the matter of the tragic death of last year's nanny, Jessie, and her boyfriend Peter. Then there's the dour housekeeper Connie and Isa's disturbing older brother Milo. Finally, there's the matter of that ghost that keeps popping up and doing mischief. Add to all that Jamie's depression and pill-addiction, and it ends up being one heck of a summer.

Until about halfway through the novel, the tension keeps winding tighter and tighter. However, with the introduction of some local teens with whom Jamie interacts, the plot loses some of its tantalizing claustrophobic menace and becomes more mundane. The spookiness ratchets up a notch towards the end, when the reader finally realizes just how unreliable a narrator our Jamie is - but then fizzles out over the anticlimactic last chapter, which could easily have been left off to much better effect.

There are some unanswered questions for readers to ponder - what is really going on at Skylark? Are all the ghostly activities just in Jamie's head? And what's up with Isa, anyway?

Jamie's voice is compelling and will keep most teens reading breathlessly to the very end of the book - especially those who have never read Turn of the Screw. As for my daughter, she snatched Turn of the Screw off our bookshelf after I described it; whether she'll read Tighter as well remains to be seen.

Recommended as a mildly spooky psychological thriller for ages 14 and up.

"You'll have to give this book a try when I'm done with it," I told my 17-year-old when I was halfway through Tighter. "It's creepy - kind of a modern version of Henry James' Turn of the Screw." Which she hasn't read - but after hearing the plot, she agreed that Tighter might be worth a try.

It starts out most promisingly, with a troubled 17-year-old girl named Jamie getting what sounds like a cushy summer job babysitting a rich 11-year-old girl named Isa on a ritzy resort island in New England. Naturally, there has to be a catch. First there's the matter of the tragic death of last year's nanny, Jessie, and her boyfriend Peter. Then there's the dour housekeeper Connie and Isa's disturbing older brother Milo. Finally, there's the matter of that ghost that keeps popping up and doing mischief. Add to all that Jamie's depression and pill-addiction, and it ends up being one heck of a summer.

Until about halfway through the novel, the tension keeps winding tighter and tighter. However, with the introduction of some local teens with whom Jamie interacts, the plot loses some of its tantalizing claustrophobic menace and becomes more mundane. The spookiness ratchets up a notch towards the end, when the reader finally realizes just how unreliable a narrator our Jamie is - but then fizzles out over the anticlimactic last chapter, which could easily have been left off to much better effect.

There are some unanswered questions for readers to ponder - what is really going on at Skylark? Are all the ghostly activities just in Jamie's head? And what's up with Isa, anyway?

Jamie's voice is compelling and will keep most teens reading breathlessly to the very end of the book - especially those who have never read Turn of the Screw. As for my daughter, she snatched Turn of the Screw off our bookshelf after I described it; whether she'll read Tighter as well remains to be seen.

Recommended as a mildly spooky psychological thriller for ages 14 and up.

The lure of jammies

Right now I could be downtown at the Central Library seeing Colson Whitehead speak, but though I quite liked The Intuitionist and enjoyed Sag Harbor up until I got bored with it - AND though I'd love to be the sort of person who partakes in the cultural life of the city - well, shameful truth be told, I'd rather be at home in my jammies reading Zone One than hearing the author talk about it. I'm a hermit at heart.

Strangely, this doesn't hold true for children's and YA authors, which is why I'll be at the Children's Literature Council Fall Gala on Saturday, November 5th, hearing Lois Lowry speak and schmoozing with plenty of other authors as well as librarians and teachers and children's literature fans of all kinds.

It doesn't hurt that it's a daytime event, so there isn't that longing for jammies that generally hits me about 8 pm...

Strangely, this doesn't hold true for children's and YA authors, which is why I'll be at the Children's Literature Council Fall Gala on Saturday, November 5th, hearing Lois Lowry speak and schmoozing with plenty of other authors as well as librarians and teachers and children's literature fans of all kinds.

It doesn't hurt that it's a daytime event, so there isn't that longing for jammies that generally hits me about 8 pm...

Sunday, October 23, 2011

Review of The Apothecary by Maile Meloy

Meloy, Maile. The Apothecary. Putnam, 2011.

It's 1952 and 14-year-old Janie's parents have just been blacklisted, which means a move for the whole family from Los Angeles to London. Janie experiences major culture shock - not only is post-war London gray, cold and drab, but also they have to put pennies in a meter just to heat their flat, there is still rationing, and the students at her new school are learning Latin.

Mostly, the students seem fairly snobby, but one boy, Benjamin, appeals to Janie. Intense and defiant, he wants to be a spy, not an apothecary like his father - but his father, it turns out, is much more than a simple dispenser of drugs and medicaments. Rather, he is one in a long line of apothecaries who have guarded the hard-won secrets of herbal and medicinal lore, all of which have been written down in an old tome called the Pharmacopoeia.

The Soviets, aided by the East Germans, want to get their hands on these secrets and will stop at nothing, including torture and murder, to get them. Janie and Benjamin join forces with a small bunch of eccentric and brilliant scientists, plus a street-smart urchin named Pip, to preserve those secrets and save the world from the threat of nuclear war.

Clearly there are familiar elements here, with bits and pieces reminiscent of The Da Vinci Code, Rick Riordan's Percy Jackson and Kane Chronicles series, Baccalario's Century Quartet series, and even N.D. Wilson's recent The Dragon's Tooth. Ancient knowledge must be kept out of the hands of the bad guys, and only a couple of intrepid kids and a few trustworthy adults can save the world from Evil.

So yes, it's been done before. But what makes this book stand out is the freshness and competence of the writing, which sparkles with both humor and warmth. Meloy has a gift for introducing a scene in just a few perfect sentences, giving us an immediate sense of both place and emotional resonance. Here is Janie describing her first day at school.

This isn't supposed to be a fantasy; it's science, not magic, that creates all the fantastical effects. However, any potion that can turn children into birds or make them invisible counts as magic in my book, so let's call this a fantasy and not science fiction. After all, Benjamin becomes a starling while Janie becomes the very American red-breasted robin, which feels like a very magical touch.

The blossoming of romance between Janie and Benjamin is both sweet and age-appropriate, and makes the ending all the more bittersweet. And yet the end is satisfying and right, even if it's one few readers would hope for.

The plot is supremely far-fetched in almost every way, and the science or magic or whatever makes no sense whatsoever - and these are definitely flaws, when one considers the masterful plotting of a book like Stead's When You Reach Me. But they are only small imperfections when measured against the quality of the writing and the delight of Janie's adventures with Benjamin and the rest of her odd companions.

Highly recommended for ages 11 to 14.

It's 1952 and 14-year-old Janie's parents have just been blacklisted, which means a move for the whole family from Los Angeles to London. Janie experiences major culture shock - not only is post-war London gray, cold and drab, but also they have to put pennies in a meter just to heat their flat, there is still rationing, and the students at her new school are learning Latin.

Mostly, the students seem fairly snobby, but one boy, Benjamin, appeals to Janie. Intense and defiant, he wants to be a spy, not an apothecary like his father - but his father, it turns out, is much more than a simple dispenser of drugs and medicaments. Rather, he is one in a long line of apothecaries who have guarded the hard-won secrets of herbal and medicinal lore, all of which have been written down in an old tome called the Pharmacopoeia.

The Soviets, aided by the East Germans, want to get their hands on these secrets and will stop at nothing, including torture and murder, to get them. Janie and Benjamin join forces with a small bunch of eccentric and brilliant scientists, plus a street-smart urchin named Pip, to preserve those secrets and save the world from the threat of nuclear war.

Clearly there are familiar elements here, with bits and pieces reminiscent of The Da Vinci Code, Rick Riordan's Percy Jackson and Kane Chronicles series, Baccalario's Century Quartet series, and even N.D. Wilson's recent The Dragon's Tooth. Ancient knowledge must be kept out of the hands of the bad guys, and only a couple of intrepid kids and a few trustworthy adults can save the world from Evil.

So yes, it's been done before. But what makes this book stand out is the freshness and competence of the writing, which sparkles with both humor and warmth. Meloy has a gift for introducing a scene in just a few perfect sentences, giving us an immediate sense of both place and emotional resonance. Here is Janie describing her first day at school.

The school was in a stone building with arches and turrets that seemed very old to me but wasn't old at all, in English terms. It was build in 1880, so it was practically brand-new... Two teachers walking down the hall wore black academic gowns, and they looked ominous and forbidding, like giant bats. The students all wore dark blue uniforms with white shirts... I didn't have a unform yet, and wore my bright green Hepburn trousers and a yellow sweater, which looked normal in LA, but here looked clownishly out of place. I might as well have carried a giant sign saying I DON'T BELONG.Making Janie an American who finds herself in England means we get to experience all the foreignness of a different country along with her, and in addition the readers can see how different 1952 was, when the Soviet threat felt very immediate and kids had to take part in bomb drills at school.

This isn't supposed to be a fantasy; it's science, not magic, that creates all the fantastical effects. However, any potion that can turn children into birds or make them invisible counts as magic in my book, so let's call this a fantasy and not science fiction. After all, Benjamin becomes a starling while Janie becomes the very American red-breasted robin, which feels like a very magical touch.

The blossoming of romance between Janie and Benjamin is both sweet and age-appropriate, and makes the ending all the more bittersweet. And yet the end is satisfying and right, even if it's one few readers would hope for.

The plot is supremely far-fetched in almost every way, and the science or magic or whatever makes no sense whatsoever - and these are definitely flaws, when one considers the masterful plotting of a book like Stead's When You Reach Me. But they are only small imperfections when measured against the quality of the writing and the delight of Janie's adventures with Benjamin and the rest of her odd companions.

Highly recommended for ages 11 to 14.

Friday, October 21, 2011

program overhaul

Ever realize you've sunk into a rut, program-wise, and need to freshen things up? I've got a post on the ALSC Blog that mulls this over.

Wednesday, October 19, 2011

Halloween cosplay

Halloween is only a week and a half away, looming in all its orangey-black glory.

Back when I was working with actual real children in the library every day, I wouldn't dream of showing up on Halloween without a costume. Perish the thought!

But now I'm in an office all day and haven't put on a Halloween program in... oh, it must be at least 5 years.

On the other hand, my office is in Central Library, so I could wear a costume and stroll nonchalantly around the children's and teen departments. In fact, there's no excuse not to!

First choice costume - the gown worn by the Statue of Civilization, which I pass every day at work.

The two sphinxes that guard the top of the stairway are nifty, too, but that might be tough to pull off. Maybe I should just replicate the gorgeous 20's gown pictured below.

But my fave idea is still to rig up a Robe of Skulls, or in my case an old Fairy Costume of Skulls. Dozens of 1" plastic skulls are on their way to me from the Skeleton Store.

I'll just sew them on the hem of my fairy costume to create an off-kilter (as in pastel) version of My Hero:

Back when I was working with actual real children in the library every day, I wouldn't dream of showing up on Halloween without a costume. Perish the thought!

But now I'm in an office all day and haven't put on a Halloween program in... oh, it must be at least 5 years.

On the other hand, my office is in Central Library, so I could wear a costume and stroll nonchalantly around the children's and teen departments. In fact, there's no excuse not to!

First choice costume - the gown worn by the Statue of Civilization, which I pass every day at work.

The two sphinxes that guard the top of the stairway are nifty, too, but that might be tough to pull off. Maybe I should just replicate the gorgeous 20's gown pictured below.

But my fave idea is still to rig up a Robe of Skulls, or in my case an old Fairy Costume of Skulls. Dozens of 1" plastic skulls are on their way to me from the Skeleton Store.

I'll just sew them on the hem of my fairy costume to create an off-kilter (as in pastel) version of My Hero:

Monday, October 17, 2011

Kids read it; we talk about it

Children's literature - it's written for kids, and yet it's written by grown-ups, critiqued by grown-ups, studied by grown-ups, bought by grown-ups, sold by grown-ups and recommended to kids by grown-ups.

Kids read children's books - or they don't - but they don't do those other things, as a rule.

Grown-ups read children's books, too. But we are adults, and our reading experience is going to be vastly different than a child's, no matter how much we tell ourselves that when we read, we most closely approach a child-like state as we immerse ourselves in the story. And of course writers of children's books are grown-ups, and no matter how well they remember their own childhoods and what it felt like to be a child, they are no longer children.

For an intensely detailed, deep, and rather funny (in a nerdy, academic sort of way) exploration of the ways adult writers and readers bring themselves to children's literature, I highly recommend Perry Nodelman's The Hidden Adult: Defining Children's Literature. I'm noodling my way through it now and though I'm only 1/4 of the way along, my mind is already sparking with the ideas he raises.

A book that explores this theme in an entirely different way is Laura Miller's The Magician's Book: a Skeptic's Adventures in Narnia, an extremely personal but also scholarly look at the author's favorite childhood series and how her perception, knowledge, and experience of the book has utterly changed now that she is an adult. And though some things have been lost as a result, much has been gained.

Meanwhile, Liz of A Chair, a Fireplace & a Tea Cozy is one of the latest to comment on the weirdness of zipping through a gripping YA novel, only to realize that - OMG, I'm older than the protagonist's parents!!!

Now, as the parent of a 17-year-old and a 20-year-old, this is no shocker to me. But I can't help but pay close attention to how the grown-ups in a children's or YA book talk, act, and think - way more than a kid or teen reader would, most likely.

Even when I'm fully engrossed in a truly absorbing children's book and am right there with the child main character, I don't feel like a child myself. I'm an engaged reader who happens to be an adult, with all the life experiences and (sometimes more importantly) book experiences that I've accumulated. The fact that I've read thousands - and reviewed hundreds - of children's books means that I can never read "like a child" again.

Which is fine with me. I'm as addicted an adult reader as I was a child reader; if anything, I'm getting more pleasure from reading than ever.

Yet many of us adult readers care deeply about the experience that a child reader is having with a book. We librarians, writers, publishers, teachers, and parents want kids to enjoy reading for many reasons. And so at the heart of much of our endless reviewing, discussing, blogging, and critiquing is the question "will a child like this book?" But not always. Sometimes we're just having the discussion as adult readers who happen to truly enjoy this type of literature.

What is it that draws some grown-ups to children's literature? That's a subject for another post - or an entire book or three. As for me, it's in small part because I loved my books fiercely as a child and never grew out of it. But mostly it's because I love a damn good book, and children's books happen to be some of the best books in existence.

Kids read children's books - or they don't - but they don't do those other things, as a rule.

Grown-ups read children's books, too. But we are adults, and our reading experience is going to be vastly different than a child's, no matter how much we tell ourselves that when we read, we most closely approach a child-like state as we immerse ourselves in the story. And of course writers of children's books are grown-ups, and no matter how well they remember their own childhoods and what it felt like to be a child, they are no longer children.

For an intensely detailed, deep, and rather funny (in a nerdy, academic sort of way) exploration of the ways adult writers and readers bring themselves to children's literature, I highly recommend Perry Nodelman's The Hidden Adult: Defining Children's Literature. I'm noodling my way through it now and though I'm only 1/4 of the way along, my mind is already sparking with the ideas he raises.

A book that explores this theme in an entirely different way is Laura Miller's The Magician's Book: a Skeptic's Adventures in Narnia, an extremely personal but also scholarly look at the author's favorite childhood series and how her perception, knowledge, and experience of the book has utterly changed now that she is an adult. And though some things have been lost as a result, much has been gained.

Meanwhile, Liz of A Chair, a Fireplace & a Tea Cozy is one of the latest to comment on the weirdness of zipping through a gripping YA novel, only to realize that - OMG, I'm older than the protagonist's parents!!!

Now, as the parent of a 17-year-old and a 20-year-old, this is no shocker to me. But I can't help but pay close attention to how the grown-ups in a children's or YA book talk, act, and think - way more than a kid or teen reader would, most likely.

Even when I'm fully engrossed in a truly absorbing children's book and am right there with the child main character, I don't feel like a child myself. I'm an engaged reader who happens to be an adult, with all the life experiences and (sometimes more importantly) book experiences that I've accumulated. The fact that I've read thousands - and reviewed hundreds - of children's books means that I can never read "like a child" again.

Which is fine with me. I'm as addicted an adult reader as I was a child reader; if anything, I'm getting more pleasure from reading than ever.

Yet many of us adult readers care deeply about the experience that a child reader is having with a book. We librarians, writers, publishers, teachers, and parents want kids to enjoy reading for many reasons. And so at the heart of much of our endless reviewing, discussing, blogging, and critiquing is the question "will a child like this book?" But not always. Sometimes we're just having the discussion as adult readers who happen to truly enjoy this type of literature.

What is it that draws some grown-ups to children's literature? That's a subject for another post - or an entire book or three. As for me, it's in small part because I loved my books fiercely as a child and never grew out of it. But mostly it's because I love a damn good book, and children's books happen to be some of the best books in existence.

Thursday, October 13, 2011

Apples, oranges, and a happy accident

Due to a tiny snafu, the National Book Award committee nominated 6 books for the Young People's Literature category instead of 5.

Hey, more to read and love, right? And I would have been heartbroken if Chime (my review) hadn't made the list. Ooh, and both Inside Out and Back Again (my review) and Okay for Now (my review) are so good!

Haven't read the others - have you?

Hey, more to read and love, right? And I would have been heartbroken if Chime (my review) hadn't made the list. Ooh, and both Inside Out and Back Again (my review) and Okay for Now (my review) are so good!

Haven't read the others - have you?

Wednesday, October 12, 2011

Review of Breadcrumbs by Anne Ursu

Ursu, Anne. Breadcrumbs. Walden Pond Press, 2011.

5th-grader Hazel's life isn't perfect. Her dad left fairly recently, meaning (among other things) that Hazel had to leave her mellow private school and start at a public school where the boys are mean and the girls don't seem to notice her. And she feels different, mostly because she lives with one foot always in the world of fantasy - Narnia and Wonderland and a dozen other realms found only in books - but also because her white parents adopted her from India when she was a baby. Not that she's the only kid of color in her school or even the only kid adopted from another country, but still, it's just another thing that sets her apart from others.

But there's one really good thing in her life and that's Jack. Her neighbor has been her best friend since they were six years old, and now they go to the same school! But things are already a bit awkward, and when Jack gets a piece of wickedly magic glass in his eye - well, first he starts acting uncharacteristically jerk-like, and then the Snow Queen comes and takes him away to her palace. Hazel, naturally, goes off into the woods to rescue him.

Hans Christian Andersen's stories are studded throughout this fantasy, with themes not just from The Snow Queen but also The Little Match Girl, The Red Shoes, The Wild Swans, The Nightingale, and probably others as well. Fantasy readers will also recognize mention of more recent books from When You Reach Me by Rebecca Stead to the Narnia books to Pullman's His Dark Materials series. And like Andersen's stories, the adventures that befall Hazel range from ominous to creepy to downright dangerous. Hazel proves herself up to all the hazing, but she doesn't escape unscathed. Not only does she receive a nasty facial wound (that does NOT magically heal), but she also learns some rather tough lessons about human nature. The woods seem to bring out the worst in people, as Hazel discovers.

Hazel's time in the woods is so vivid and horrifying that it rather makes her trials with 5th-grade boys and impatient teachers feel light and not quite real by comparison. There are some loose ends; for example, a couple of visits with a girl named Adelaide and her nifty uncle seem destined to be important plot points later in the story, but they never fulfill this promise. And the final rescue of Jack from the Snow Queen is hurried and anti-climactic after all that came before. Readers may be wondering why Hazel went to all that bother in the first place, as Jack's worth is never proven to us, glass shard or no glass shard. We just have to take Hazel's rose-colored assertion that he is her heart's companion.

Of course, the point is that, now that Hazel has successfully completed her quest, she can now look beyond Jack - and her childhood - and start broadening her horizons. There is Adelaide, there are some promised ballet lessons, there are even those 5th-grade boys, who maybe aren't as bad as Hazel thought. Hazel has found herself more than a match for the world and she's ready to really live.

This stands up very well to Gardner's Into the Woods and similar fantasies, and though it doesn't match the caliber of Gidwitz's A Tale Dark and Grimm, Breadcrumbs is highly recommended for ages 9 to 11.

5th-grader Hazel's life isn't perfect. Her dad left fairly recently, meaning (among other things) that Hazel had to leave her mellow private school and start at a public school where the boys are mean and the girls don't seem to notice her. And she feels different, mostly because she lives with one foot always in the world of fantasy - Narnia and Wonderland and a dozen other realms found only in books - but also because her white parents adopted her from India when she was a baby. Not that she's the only kid of color in her school or even the only kid adopted from another country, but still, it's just another thing that sets her apart from others.

But there's one really good thing in her life and that's Jack. Her neighbor has been her best friend since they were six years old, and now they go to the same school! But things are already a bit awkward, and when Jack gets a piece of wickedly magic glass in his eye - well, first he starts acting uncharacteristically jerk-like, and then the Snow Queen comes and takes him away to her palace. Hazel, naturally, goes off into the woods to rescue him.

Hans Christian Andersen's stories are studded throughout this fantasy, with themes not just from The Snow Queen but also The Little Match Girl, The Red Shoes, The Wild Swans, The Nightingale, and probably others as well. Fantasy readers will also recognize mention of more recent books from When You Reach Me by Rebecca Stead to the Narnia books to Pullman's His Dark Materials series. And like Andersen's stories, the adventures that befall Hazel range from ominous to creepy to downright dangerous. Hazel proves herself up to all the hazing, but she doesn't escape unscathed. Not only does she receive a nasty facial wound (that does NOT magically heal), but she also learns some rather tough lessons about human nature. The woods seem to bring out the worst in people, as Hazel discovers.

"She saw signs of another village in the distance - she smelled smoke and saw the faint glow of something like civilization. But there was nothing for her there. She had to go get Jack now, and anyway, she was safer out here with the wolves."Hazel's habit of never paying much attention to boring stuff around her (her parents, her teachers) doesn't stand her in good stead in the magical woods, when she wishes she knew a few survival tips. Towards the end, when she is very cold and with few resources left, she has shed her dreamy escapist tendencies in favor of a more practical, realistic viewpoint. "This is what it is to live in the world. You have to give yourself over to the cold, at least a little bit."

Hazel's time in the woods is so vivid and horrifying that it rather makes her trials with 5th-grade boys and impatient teachers feel light and not quite real by comparison. There are some loose ends; for example, a couple of visits with a girl named Adelaide and her nifty uncle seem destined to be important plot points later in the story, but they never fulfill this promise. And the final rescue of Jack from the Snow Queen is hurried and anti-climactic after all that came before. Readers may be wondering why Hazel went to all that bother in the first place, as Jack's worth is never proven to us, glass shard or no glass shard. We just have to take Hazel's rose-colored assertion that he is her heart's companion.

Of course, the point is that, now that Hazel has successfully completed her quest, she can now look beyond Jack - and her childhood - and start broadening her horizons. There is Adelaide, there are some promised ballet lessons, there are even those 5th-grade boys, who maybe aren't as bad as Hazel thought. Hazel has found herself more than a match for the world and she's ready to really live.

This stands up very well to Gardner's Into the Woods and similar fantasies, and though it doesn't match the caliber of Gidwitz's A Tale Dark and Grimm, Breadcrumbs is highly recommended for ages 9 to 11.

Monday, October 10, 2011

The Meaning of Life

|

| StingRay meets Lumphy for the first time |

I assume, based on Plastic's bouncy toddler/preschooler persona (she's a plastic ball who asks lots of questions), that what Plastic was really asking was "What confluence of events brought us to exactly this place in this moment of time?" This can be a dizzying question - but I bet if StingRay had mustered the patience and creativity to answer it in sufficient detail ("well, I'm here because I was given to the Girl for her birthday last year and you are here because you were a party favor for her birthday this year and..."), Plastic would have been satisfied. Sure, there would have been more follow-up "but WHY"s than anyone could tolerate for long, but eventually Plastic would have found some other question to ask.

This isn't the question that so filled Lumphy with Dread. Rather, Lumphy couldn't bear the corollary question, which is "And now what?" In other words, now that we're here due to some dizzying and incomprehensible sequence of events, how do we proceed? Is there any meaning to the fact that we're here? If so, what is it? How do we find it?

Plenty of young kids will understand Plastic's need to have the first question answered. But few kids under the age of, say, 10 or 12 would even recognize the existence of Lumphy's dreaded questions, much less understand his terror of it.

Or so I assume, using my own childhood and that of my daughters as my main reference points. My kids had plenty of questions when they were little, some of which produced anguish, but they tended to be along the lines of "Should I wear the blue t-shirt or the yellow t-shirt?" or "Why does cookie batter taste so good but make you throw up if you eat the whole bowl?" There were no abstract or existential questions until they were into their double-digits.

The first time I remember being shaken by abstract ideas beyond my small and concrete world was while watching a sunset at the beach (I know - kinda trite) when I was about 11 or 12. It suddenly struck me that the beauty I was witnessing was a Big Thing that couldn't be fully contained or expressed, and this realization expanded my soul in one enormous bang.

So I'd love to know what 8-year-old readers think of Lumphy's nights of dread and wondering. Can they understand? Do they get it? Even if they don't, they will certainly feel that the answer Lumphy finally gets from his friends is an apt one - "We are here for each other."

All this thinking was caused by this hillside, which we passed while on a long hike up to the Nordhoff Lookout in the mountains just north of Ojai. First I had my usual moment of regret about my huge ignorance of geology - all those cool striations, tilted like a dropped layer cake, and I have no idea what the layers are composed of or how they were formed.

But I do know that it took a LONG TIME for the layers to form, and another LONG TIME for this section of hillside to bulge and thrust up the way it has. And this is when I start to feel my own form of Dread - because there I am, crawling like the tiniest bug along this ancient hill that is attached to the even more ancient Earth, that is a part of a universe so vast and old that my heart starts racing just to think about it.

And as I contemplated the terror of this literally unthinkable, incomprehensible hugeness of space and time, I was also very aware of the path I was walking on and the smell of the sage and other bushes and the new view that unfolded with every curve of the path and the stupid bee that buzzed in my ear ALL the way up to the summit. And all these things were adding up to a very lovely hike (well, except the bee).

Suddenly, the idea that my mind could be simultaneously wheeling around in the unfathomable wonders of the universe AND taking pleasure in the crunch of my shoes on the rocky path filled me with a kind of blissed-out giddiness.

(Meanwhile, my husband was getting farther and farther ahead of me. Sure, he was carrying the backpack stuffed with all our food and water - but I was burdened by these Very Weighty Thoughts.)

Remember R.L. Stevenson's Happy Thought? "The world is so full of a number of things, I'm sure we should all be as happy as kings." As a child, I begged to differ (understanding it, as a child does, very literally). But though it seems to be a naive sentiment that ignores the great suffering in the world, there is a great truth at its core. Surely it is a good idea to cultivate an enjoyment for the simple things in life, as well as wonder in the big things.

There's no one answer to "Why are we here?" but maybe the point is to keep on asking the question and looking for answers. And to live one's life according to the answers we come up with.

"We are here for each other" will do very nicely as one of those answers. Lumphy has good friends.

Friday, October 7, 2011

Review of Toys Come Home by Emily Jenkins

Jenkins, Emily. Toys Come Home. Schwartz & Wade Books, 2011.

This prequel to the magnificent Toys Go Out and Toy Dance Party depicts the arrival of StingRay (a stuffed stingray, naturally) to the Little Girl's house and her gradual assimilation into the household, where she lives with the other sentient toys and objects, from a pompous walrus named Bobby Dot to a wise old towel named TukTuk.

StingRay, who is very smart and rather complicated, is a good soul at heart (she rescues Sheep from a terrible predicament, at great personal risk) but she does suffer from uncharitable and petty thoughts. She prefers that the others think she knows everything (and will make stuff up so as not to destroy their illusions), and she can't help but think "better him than me" when the demise of Bobby Dot means that StingRay gets to sleep on the Girl's bed with her.

But it's Lumphy the buffalo (such a sweet and brave guy) who truly suffers existential Angst, brought on by the newly arrived and irrepressible Plastic asking "Why are we here?...Why are we here in the Girl's room? In this town, on this planet?" StingRay can't answer, of course and so sputters "I'll tell you later. Right now I have some important stuff to do."

But poor Lumphy can't stop wondering about the question - it keeps him up at night, worrying. He has Dread, which, he explains to Plastic, "...has to do with too much dark. And not knowing why we're here. And not sleeping."

Jeepers! Truly, can anything be better than a story with lovingly drawn characters (not just figuratively - Zelinsky's illustrations are pretty darn good), hair-raising adventure, pathos, humor, Big Philosophical Questions, AND a 3rd-grade reading level? I think not.

Highly recommended, as are the other two books in this trilogy, for all ages ('cause it makes a great read-aloud for younger kids as well).

This prequel to the magnificent Toys Go Out and Toy Dance Party depicts the arrival of StingRay (a stuffed stingray, naturally) to the Little Girl's house and her gradual assimilation into the household, where she lives with the other sentient toys and objects, from a pompous walrus named Bobby Dot to a wise old towel named TukTuk.

StingRay, who is very smart and rather complicated, is a good soul at heart (she rescues Sheep from a terrible predicament, at great personal risk) but she does suffer from uncharitable and petty thoughts. She prefers that the others think she knows everything (and will make stuff up so as not to destroy their illusions), and she can't help but think "better him than me" when the demise of Bobby Dot means that StingRay gets to sleep on the Girl's bed with her.

"The joy, the guilt, the loss, and the relief: all these feelings toss around inside her in the night..."Oh StingRay - been there, honey!

But it's Lumphy the buffalo (such a sweet and brave guy) who truly suffers existential Angst, brought on by the newly arrived and irrepressible Plastic asking "Why are we here?...Why are we here in the Girl's room? In this town, on this planet?" StingRay can't answer, of course and so sputters "I'll tell you later. Right now I have some important stuff to do."

But poor Lumphy can't stop wondering about the question - it keeps him up at night, worrying. He has Dread, which, he explains to Plastic, "...has to do with too much dark. And not knowing why we're here. And not sleeping."

Jeepers! Truly, can anything be better than a story with lovingly drawn characters (not just figuratively - Zelinsky's illustrations are pretty darn good), hair-raising adventure, pathos, humor, Big Philosophical Questions, AND a 3rd-grade reading level? I think not.

Highly recommended, as are the other two books in this trilogy, for all ages ('cause it makes a great read-aloud for younger kids as well).

Wednesday, October 5, 2011

Alone but not lost

Back in the Before Time when I was in college, a certain very young and intense man read this passage from Thomas Wolfe's Look Homeward, Angel to me; it's from the point of view of the main character Eugene as a baby in his crib:

And while I in turn was moved by this young man's passion for literature (Reader, I married him), these particular sentiments left me cold. My feeling was that this eternal separation from others, this inability to ever completely know another being, was essential to sanity and happiness.

26 years later, I still feel that way. My own skull isn't my prison; it's my refuge. Interaction with people, whether it's superficial or deep, can be exhausting and fraught - being alone in my head is a saving grace, not a tragedy.

Of course, sometimes it's not so fun being trapped with oneself, unable to escape one's thoughts and very existence. In that case there are only 3 possible remedies for me:

And going back to Wolfe and his despair, running as a constant theme through all his books, at the human failure to every truly know or communicate with others (in another passage, this one from Of Time and the River, a character wonders "What is wrong with people?...Why do we never get to know one another? ...Why is it that we get born and live and die here in this world without ever finding out what any one else is like?") - well, I submit that reading books is a fine way to get to know one another (especially for us natural-born hermits).

An author is setting down carefully crafted words that communicate thoughts and ideas and visions and stories that can resonate deeply with readers. Books communicate truths both mundane and profound; I've never thought so much about what it means to be human as when reading books. I may not be getting to know those writers personally, but we are sharing ideas and concepts that go deeper than that.

And even a "frivolous" story well-told can spark associations and ideas for days, weeks, and years after the book has returned to the library and almost forgotten.

Some of us are like Thomas Wolfe, always striving outward, always yearning for meaningful human connection from the people they meet, constantly seeking out true companions.

And some of us would rather be reading.

*My husband read that passage aloud again to me a couple nights ago, this time with melodramatic flair, laughter, and some nostalgia for the young man he used to be. But he added that he still understands and agrees with the sentiment, though he doesn't feel it with quite the same Weltschmerz that he used to.

...he knew he would always be the sad one: caged in that little round of skull, imprisoned in that beating and most secret heart, his life must always walk down lonely passages. Lost. He understood that men were forever strangers to one another, that no one ever comes really to know any one, that imprisoned in the dark womb of our mother, we come to life without having seen her face, that we are given to her arms a stranger, and that, caught in that insoluble prison of being, we escape it never, no matter what arms may clasp us, what mouth may kiss us, what heart may warm us. Never, never, never, never, never.This young man felt that this and other similar passages in Wolfe's books were very profound and moving indeed, and they touched him deeply.*

And while I in turn was moved by this young man's passion for literature (Reader, I married him), these particular sentiments left me cold. My feeling was that this eternal separation from others, this inability to ever completely know another being, was essential to sanity and happiness.

26 years later, I still feel that way. My own skull isn't my prison; it's my refuge. Interaction with people, whether it's superficial or deep, can be exhausting and fraught - being alone in my head is a saving grace, not a tragedy.

Of course, sometimes it's not so fun being trapped with oneself, unable to escape one's thoughts and very existence. In that case there are only 3 possible remedies for me:

- Mindfulness meditation (if I could ever make myself practice it regularly enough to get competent at it)

- Running (in a miraculous alchemy, stressful thoughts transform into invigorating adrenaline)

- Reading

And going back to Wolfe and his despair, running as a constant theme through all his books, at the human failure to every truly know or communicate with others (in another passage, this one from Of Time and the River, a character wonders "What is wrong with people?...Why do we never get to know one another? ...Why is it that we get born and live and die here in this world without ever finding out what any one else is like?") - well, I submit that reading books is a fine way to get to know one another (especially for us natural-born hermits).

An author is setting down carefully crafted words that communicate thoughts and ideas and visions and stories that can resonate deeply with readers. Books communicate truths both mundane and profound; I've never thought so much about what it means to be human as when reading books. I may not be getting to know those writers personally, but we are sharing ideas and concepts that go deeper than that.

And even a "frivolous" story well-told can spark associations and ideas for days, weeks, and years after the book has returned to the library and almost forgotten.

Some of us are like Thomas Wolfe, always striving outward, always yearning for meaningful human connection from the people they meet, constantly seeking out true companions.

And some of us would rather be reading.

*My husband read that passage aloud again to me a couple nights ago, this time with melodramatic flair, laughter, and some nostalgia for the young man he used to be. But he added that he still understands and agrees with the sentiment, though he doesn't feel it with quite the same Weltschmerz that he used to.

Monday, October 3, 2011

Review of Junonia by Kevin Henkes

Henkes, Kevin. Junonia. Greenwillow, 2011.

The world of an only child is filled with grown-ups, or at least that's the case for Alice during an annual vacation in Florida. Generally there are other kids as well, but not this year, the year she is turning 10 years old. This year, the only other kid is the problematic Mallory, the 6-year-old daughter of Alice's Aunt Kate's new boyfriend.

So Alice spends her vacation, and her birthday, having attention lavished on her by the adults around her - but also having to be mature herself when relating to the troubled Mallory, who misses her far-away mom. It's not always easy for Alice, who finds herself full of resentment and hurt when ancient Mr. Barden remarks that Mallory is the prettiest girl he ever saw. But conquering her irritation and doing the right thing turns out to have its own rewards.

This is a quiet book on the surface, but full of the heaving emotions that can boil in sensitive people of any age, often unexpectedly or even inexplicably. It feels a bit claustrophobic and intense at times; you just want Alice to be able to run along the seashore joyfully without being jostled about by currents of annoyance or sadness or disappointment or anger. And she does, actually, but never for long - for small things do seem mighty fraught in Alice's life. Perhaps it comes of being the only child of older parents and of having an aunt with no kids of her own, plus plenty of other adults in her life who spend a fair amount of their time thinking and caring about her.

The writing is beautiful and Alice's emotions are genuine and age-appropriate - but this feels like a grown-up book nonetheless. Perhaps it was sentences like this one that took me out of Alice's head and made me feel like an adult observer - "She was loose jointed, and although she felt awkward much of the time, she often appeared graceful." No kid would think about about herself or any other kid.

Thoughtful, introspective children may well feel that they've found a soul-mate in Alice, but even these kids may crave a tiny bit more action.

For ages 8 to 11.

The world of an only child is filled with grown-ups, or at least that's the case for Alice during an annual vacation in Florida. Generally there are other kids as well, but not this year, the year she is turning 10 years old. This year, the only other kid is the problematic Mallory, the 6-year-old daughter of Alice's Aunt Kate's new boyfriend.

So Alice spends her vacation, and her birthday, having attention lavished on her by the adults around her - but also having to be mature herself when relating to the troubled Mallory, who misses her far-away mom. It's not always easy for Alice, who finds herself full of resentment and hurt when ancient Mr. Barden remarks that Mallory is the prettiest girl he ever saw. But conquering her irritation and doing the right thing turns out to have its own rewards.

This is a quiet book on the surface, but full of the heaving emotions that can boil in sensitive people of any age, often unexpectedly or even inexplicably. It feels a bit claustrophobic and intense at times; you just want Alice to be able to run along the seashore joyfully without being jostled about by currents of annoyance or sadness or disappointment or anger. And she does, actually, but never for long - for small things do seem mighty fraught in Alice's life. Perhaps it comes of being the only child of older parents and of having an aunt with no kids of her own, plus plenty of other adults in her life who spend a fair amount of their time thinking and caring about her.

The writing is beautiful and Alice's emotions are genuine and age-appropriate - but this feels like a grown-up book nonetheless. Perhaps it was sentences like this one that took me out of Alice's head and made me feel like an adult observer - "She was loose jointed, and although she felt awkward much of the time, she often appeared graceful." No kid would think about about herself or any other kid.

Thoughtful, introspective children may well feel that they've found a soul-mate in Alice, but even these kids may crave a tiny bit more action.

For ages 8 to 11.

Sunday, October 2, 2011

Visions of sugarplums

To find out how some of my LAPL colleagues and I spent the summer, check out our School Library Journal reviews of December Holiday Books.

And bring on the eggnog, heavy on the rum!

And bring on the eggnog, heavy on the rum!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)